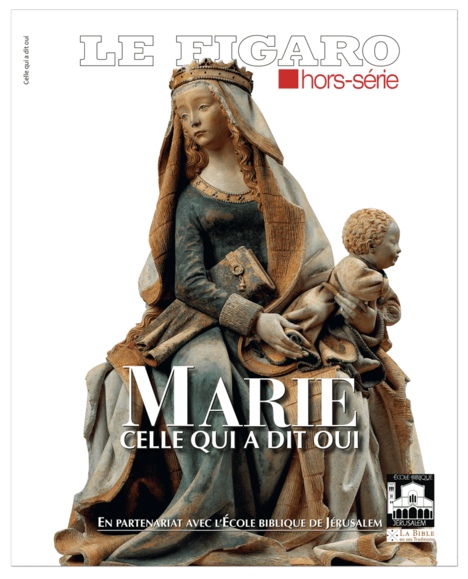

After two issues in partnership with the École Biblique (Le roman de la Bible and Jésus Christ, cet inconnu), Le Figaro Hors-série is dedicating an issue this time to the Mother of God: Marie, celle qui a dit oui. Five residents of Saint-Etienne convent participated in the construction of this issue by writing an article for the magazine. We look back with them at the themes addressed:

Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple, Capella degli Scrovegni (Padua, Italy)

“We always show how Jesus fulfils all the promises that were made to Israel. This is called typological reading: we try to find in the Old Testament everything that announces Jesus. The same thing can be done with the Virgin Mary, meaning that the Virgin Mary, “the daughter of Zion”, is also announced in the Old Testament (the prophet Zephaniah, Zechariah, Micah or the prophet Isaiah). The daughter of Zion is a form of personification of Israel, but it is also more than that. The Virgin Mary also comes to fulfil the promises made to Israel, she, the daughter of Zion. So there is a form of continuity between Mary as a figure of Israel, but also Mary as a figure of the end of time for Israel.

What I am trying to show in this article is how Mary, daughter of Israel, because she is a daughter of her people in a certain way, did not become the Mother of God just because an angel came to her one day. In the Protoevangelium of James, an apocryphal text that has not been retained in the canon but that has had an extreme influence on all European art, the story of Mary as a child and her consecration to the Temple is told. Mary was a virgin consecrated to the Temple, she lived in the Temple as a child, etc. The liturgical feast of the presentation of the Virgin Mary in the Temple, which is celebrated in Catholicism and in Orthodoxy, has been kept. There is therefore a whole tradition around the Virgin Mary which shows how she was prepared to become the mother of Jesus, which is not directly in the Gospel but which can be found in the history of art: at the Annunciation, when the angel Gabriel comes to see Mary, she is reading. It is by meditating on the scriptures and the promises made to Israel that she is able to accept this enormous thing.

Putting Mary, like Jesus, back into the Jewish context of the time, gives more importance to the incarnation which is central. If Jesus is incarnated it is in a people, with a culture. Passages that seem a little legendary or strange about the Virgin Mary are no longer so in the light of the scriptures. She comes to fulfil, like Jesus, the promises made to Israel.

It was very pleasant to work with Figaro Magazine, because they are professional people from a journalistic point of view but also from a biblical and Christian point of view. We were able to discuss and have an interesting exchange, which allowed me to re-specify certain points in my article. It was a great collaboration.”

Réjouis-toi, fille de Sion (p. 50-57), fr. Olivier Catel, op

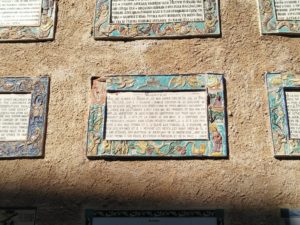

The Magnificat displayed in 67 languages at the Church of the Visitation in Ein Karem (west of Jerusalem).

“The Magnificat is the prayer of Mary in the Gospel of St Luke: “My soul magnifies the Lord…”.

St Luke is quite musical, several songs are present in the story of Jesus’ childhood. The Magnificat must therefore be seen in this context: around the Benedictus and the song of Simeon. This metaphor of music is an entry point for understanding the story. In this passage of the Gospel, the action stops to allow the characters to reflect on what is happening.

There are several echoes of this passage. It is closely related, for example, to another prayer in the Old Testament: the song of Hannah (1 Samuel 2:1-10), who is also a childless woman. This canticle is a kind of poem, a song, very similar to Mary’s prayer. These links are interesting especially because they underline the differences between the two: for example, Hannah in the Old Testament always speaks of the future “God will exalt the body of his Messiah”, the last word of this prayer is Messiah, so it is a prophecy towards the future. Mary, on the other hand, speaks in the past tense, she has already done something. So it’s a kind of call and response between the two. New Testament and Old Testament. It’s quite subtle, but it’s a way of understanding what Mary is saying. There are several echoes, but this one is the most important.

The Magnificat belongs to an artistic licence of the evangelist Luke, Mary is not expected to launch into long, complicated poems like this. It is a thoughtful composition, but few scholars believe that Luke himself invented this poem, which he probably received from an earlier tradition. This prayer is quite interesting on a historical and theological level since the Marian voice and the voice of the Church are intertwined. On the historical level, it is the Church that takes Mary’s voice and still prays her words today. Theologically, there are several variants of the Magnificat, such as Monteverdi’s, and all of them distribute the word to several people. It is never a solo but always a choir that sings. The Mother of God should not be isolated or separated from the whole Church to which she belongs.”

Magnificat (p. 58-61), fr. Anthony Giambrone, op

Believers praying in the cave of the Nativity in Bethlehem.

The list of archaeological sites dedicated to the Virgin Mary in the Holy Land is long. Fr. Dominique-Marie Cabaret discusses the authenticity of these sites in his article in the Figaro. Here he focuses on the most important sites for him as an archaeologist and as a Dominican:

“As an archaeologist, I like the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem. It is one of the oldest churches in the world still in use, as it was rebuilt in the 6th century. Its five naves, its monolithic columns, its architraves, its beautiful capitals, … It is a unique construction method. Few churches from this period are still in use. The Tomb of the Virgin is interesting for the same reason: it is a 5th century church with a beautiful Byzantine vault. As an archaeologist, these are the most extraordinary of all the sites dedicated to the Virgin Mary. The others have been dismantled, reassembled, burnt, transformed into mosques, …

From a Dominican point of view, the most important is undoubtedly the Tomb of the Virgin, the place of the Assumption, since there was a resurrection. Of the many mysteries in the life of the Virgin Mary, the Assumption is one that touches me the most, and Mary’s Tomb is the only place where this event is venerated.

The age of the buildings touches my historical fibre. As an archaeologist and a believer, the age of the shrine matters: the older the shrine, the more people have been there. You can feel the weight of the prayer of those who have passed through for centuries, which is not the case in more modern buildings. There is a spiritual dimension and there is a community. St Paul speaks of the church as the body of Christ. It is not a body in the physical sense, but a unity. It is in this sense that the prayers of the Christians of 1500 or 2000 years ago also have weight.

It is not just the old stones, it is the beauty of the old stones and the dimension of the spiritual body that has been developed in these churches that counts for me.”

Marie, la discrète (p. 62-67), fr. Dominique-Marie Cabaret, op

The Virgin of the Apocalypse, Miguel Cabrera

“I quickly answered “yes” to the request of our friends at Le Figaro to propose to contributors to the Bible en ses Traditions that they write for a new special series of a biblical nature, this time on the Virgin Mary, after the first two, on the Old Testament, and on Jesus Christ. Indeed, isn’t Mary, the holy Mother of God, a model for every biblical scholar? She is the one who intelligently questions, without questioning the divine Word, from the Annunciation onwards, she is the one who “keeps these things and meditates on them in her heart” throughout the Gospel… to keep, to question, to deepen in order to try to understand, never to cease to believe, what a model for us!

On a personal note, I have been focusing on an enigmatic figure in the Apocalypse. In chapter 12 of the Apocalypse of Saint John, there is the famous image of a woman, crowned with stars, tortured by the pains of childbirth, and threatened by a dragon. Like the rest of the Apocalypse, this image unfolds the magnificent symbolism of a struggle that is that of the last times. Much of the Christian tradition has seen the vision of the woman as a representation of the Virgin Mary and her son, the incarnate Word… However, there are also reasons for not seeing the Virgin Mary in it. If one believes, according to dogma, that the Virgin Mary is a virgin before, during and after her birth and that she is free from original sin (according to the Bible, the pains of childbirth are directly linked to sin: “For this reason you will give birth in pain”), then one must think that Mary did not give birth in pain. This text is therefore interesting because it poses this fundamental question: who is this woman, and what is she the symbol of?

Besides the Marian interpretation (this woman is the Virgin Mary), there are two other main interpretations: the spiritual interpretation (this woman represents every soul on the way to God, threatened by the evil one), and the ecclesial interpretation (ecclesia meaning community): this woman symbolises the community of the Church, the community of all those who believe in Jesus.

It turns out that the Apocalypse of John and the Fourth Gospel (“according to John”) form a corpus. So there is a tendency to project the Gospel of John into the reading of Revelation, and it turns out that in the Gospel of John, the Mother of Jesus has an extremely important role. It is she who precipitates the revelation of Jesus at the wedding feast in Cana. She is the catalyst for the manifestation of her son. We find her later at the bottom of the cross with Saint John. Jesus, dying, entrusts them to each other, saying: “Woman, this is your son; son, this is your mother”. In Tradition it has remained that the Blessed Virgin spent the last years of her life under the protection of St John. With this in mind, when reading the description of this woman in the Apocalypse of John, it is quite easy to understand this woman as Mary mother of the Church, who continues to give birth to believers, as “sons” in the footsteps of Saint John. The representation of the community by a woman was common in Judaism, as in the case of the “daughter of Zion”.

According to the Apocalypse, St. John was exiled to the island of Patmos (in Greece) at the time of his vision, during one of the persecutions that shook the early Christian world. On Patmos, the myth of Leto is widely spread: Leto, by the work of Zeus, pregnant by Apollo and Artemis, must flee the wrath of Hera, the wife of Zeus, who has sent the serpent Python to persecute her. He knows from a prophecy that Leto’s son will kill him. Leto hides on an island and gives birth to Apollo and Artemis. A few days later, the latter fulfils the prophecy and kills Python. There is therefore, in the mythology of this region, a story that may also have inspired the Apocalypse…

Thus the vision of the woman in Revelation 12 condenses at the same time a “pagan” inspiration, a “Jewish” inspiration and the story of Jesus (… and of his mother!), in such a way that only the Holy Spirit could have inspired this brilliant visionary of the first century!”

Couronnée d’étoiles (p. 104-111), fr. Olivier-Thomas Venard, op

The Tomb of the Virgin Mary, where, according to tradition, the Assumption took place.

“As you probably know, I was a Protestant. That is why Le Figaro asked me to write this article about the position of the Reformed Church towards the Virgin Mary.

In the history of Protestantism, we must see a traditional Protestantism, that of Luther and Calvin, and a liberal Protestantism. The Virgin Mary was not a primary concern of the Protestant Reformation. Coming from a traditional Protestant family in the Reformed Church of France, I can say that it was not a divisive issue, or even a favourite topic of discussion. In fact, Luther wrote a Commentary on the Magnificat. On the other hand, liberal Protestantism was to attack several dogmas, including the Marian dogmas.

With the Reformation, Anabaptism and major anti-Trinitarian currents developed. Baptism became a subject of dispute among the reformers, as did the Trinity and the Lord’s Supper (the Eucharist). Calvin had Michel Servet, a Spanish doctor, burned in Geneva because he denied the Trinity. With liberal Protestantism, the question of Mary also arose. Some will develop the idea that if Mary plays a role in the salvation of humanity, everything you give to Mary, you take away from Christ. And above all, this problem will arise which did not exist among the Reformers: was Mary a virgin before, during and after childbirth?

The distancing from Catholicism will be accentuated with the recent dogmas concerning Mary: the dogma of the Immaculate Conception, Mary was conceived without original sin; and the dogma of the Assumption, the Virgin Mary was raised in glory with her body to her son. In the Catholic Church, the dogma is not fixed but develops with tradition. The Immaculate Conception is deduced from the Theotokos (Mary is defined as Mother of God. If Mary is not the Mother of God, then this affects the status of Christ as fully man and fully God). However, these dogmas of the Immaculate Conception and the Assumption are not in the Bible, and the principle of Protestantism is the sovereign authority of the Scriptures.

There are other points of difference between Catholicism and Protestantism; for example, in the Protestant confession there is no such thing as purgatory. For a Protestant, after death in the simplest doctrine, there is no intermediary in heaven or hell. So there is no need to pray for the dead or to place remembrances in cemeteries. However, when I was a pastor in Nîmes, I saw Protestants going to the cemetery on November 1st, which is not at all in the Protestant tradition. We talk about Protestantism, but there are so many of them.

The separation between Catholicism and Protestantism was made gradually. What is the Church for the Reformation? For the Catholic, the Church is the mediator: to reach the sacrament the individual goes through the Church (confession, marriage, etc.). In Protestantism, there is no ecclesiological mediation.

The Marian question is therefore not fundamental, the real debate is about the nature of the Church.”

Le signe de contradiction (p. 116-121), fr. M-Augustin Tavardon, ocso

Fr. Renaud Silly, op, a non-resident researcher at the convent of Saint-Etienne, who notably directed the conception of the Jesus Dictionary of the Bible in its Traditions, also contributed to this issue.